What’s the problem?

Only two forms of hypothyroidism are ever considered. Primary hypothyroidism (failure of the thyroid gland) and central hypothyroidism (failure of the pituitary or hypothalamus). Primary hypothyroidism usually presents with a high TSH, central hypothyroidism with a very low TSH. Our example patients are not in either category, their TSH is subnormal but not quite enough to be called central hypothyroidism.

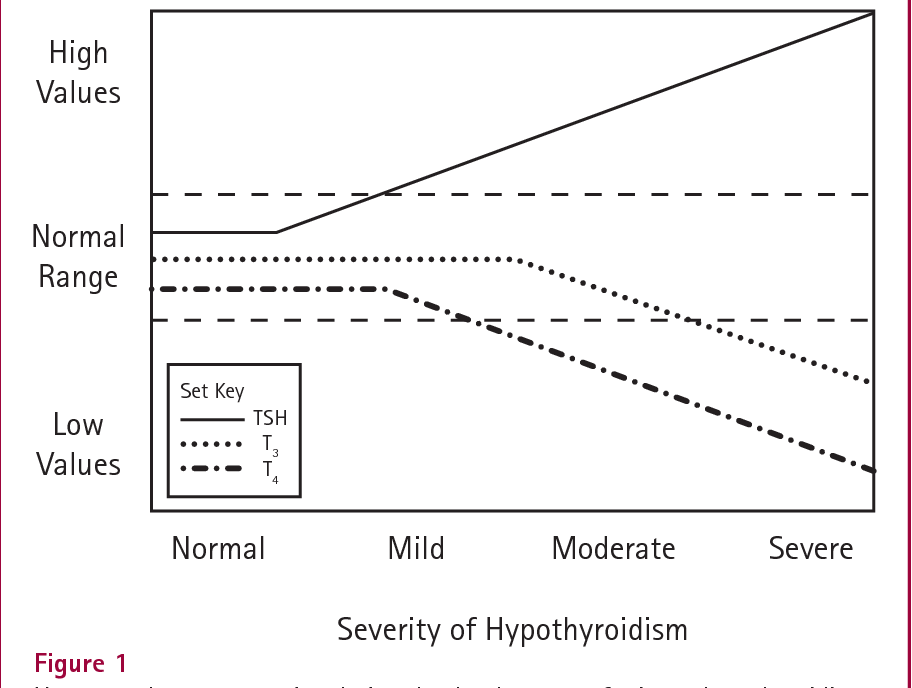

McDermott’s diagram below shows the theoretical response to primary hypothyroidism. (Note: the TSH line is incorrect, TSH increases exponentially with falling fT3 and fT4, this line should be an upward curve). As the thyroid starts to fail TSH rises rapidly whilst fT3 and fT4 stay normal. As thyroid failure progresses fT4 falls but fT3 is maintained. The high TSH stimulates the thyroid to secrete more T3 and increases the rate of conversion of T4 to T3. Eventually the thyroid packs in, fT3 falls and the patient becomes hypothyroid. Thus, in most cases TSH is a very good marker for primary hypothyroidism, it can identify thyroid failure in the early stages. TSH is invaluable in neonatal and veterinary medicine. In other forms of hypothyroidism TSH is helpful only if it is interpreted in conjunction with fT3 and fT4.

How do we know the TSH level is subnormal?

TSH has inter and intra-individual variations, it is stimulated by TRH and supressed by negative feedback from fT3 and fT4. TSH, fT3, fT4 are not independent variables and must not be treated as such. This is of fundamental importance. As can be seen in the above diagram when fT3 and fT4 are low normal the patient has moderate primary hypothyroidism and TSH will be very high – provided the patient has an intact axis. If fT3 and fT4 are borderline and TSH is not elevated the axis is not intact, TSH is subnormal.

The crucial difference is that if TSH is high there will be increased type-2 deiodinase (D2) – T4 to T3 conversion – in organs that use D2 for local T3 regulation. Local T3 levels will be maintained. ‘Where the T3 comes from’ matters!!! ‘D2T3’ has different effects to T3 coming from D1 or from the thyroid or from tablets.

Effect of Low Normal T3 on TSH

Abdalla SM, Bianco AC. Defending plasma T3 is a biological priority. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2014 Nov;81(5):633-41. doi: 10.1111/cen.12538. Epub 2014 Aug 7. PMID: 25040645; PMCID: PMC4699302.

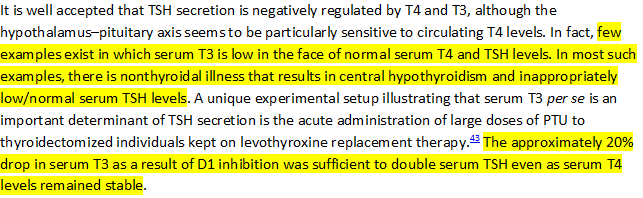

The study referenced above is pertinent because in another study propylthiouracil (PTU) was used to block type-1 deiodinase (D1) in athyreotic patients. The thyrotrophs (cells in the pituitary that produce TSH in response to TRH) do not express D1 and so would not be affected by PTU. Thus, a 20% reduction in (total) T3 levels produced a doubling of TSH. They didn’t measure free T3, but it is likely the reduction in fT3 would be no more than the reduction in total T3. T4 levels remained unchanged.

The doubling in TSH was for patients receiving 100 mcg L-T4. As can be seen in Figure 1 above these patients were under-medicated with very high TSH levels. It possible that TSH was close to its maximum for some patients. Patients who received 200 mcg L-T4 had normal TSH levels which showed a much greater rise although the fall in T3 was also greater. These results indicate that falls in T3 levels are associated with large increases in TSH. A reduction in T3 towards its lower limit is accompanied by an increase in TSH. Falling T4 levels also elevate TSH. A patient with BOTH low normal fT3 and low normal fT4 will usually have a high TSH.

What’s happening in Subnormal TSH?

Tissues receive hormone from the serum and are thus dependent upon serum levels as reflected in fT3, fT4 and TSH assays. ‘The level of T3 inside the cells defines how much T3 is bound to TR and hence the intensity of signalling‘. It is the amount of T3 getting to the thyroid hormone receptors (TR) that determines ‘thyroid status’, whether the patient is hypo or hyper-thyroid. This starts with serum free T3 and free T4 availability. If both fT3 and fT4 are low normal the patient will be hypothyroid.

In reality these patients have even more severe hypothyroidism than might be expected from combined low normal fT3 and fT4. To understand why this is so we must look at where the T3 is coming from.